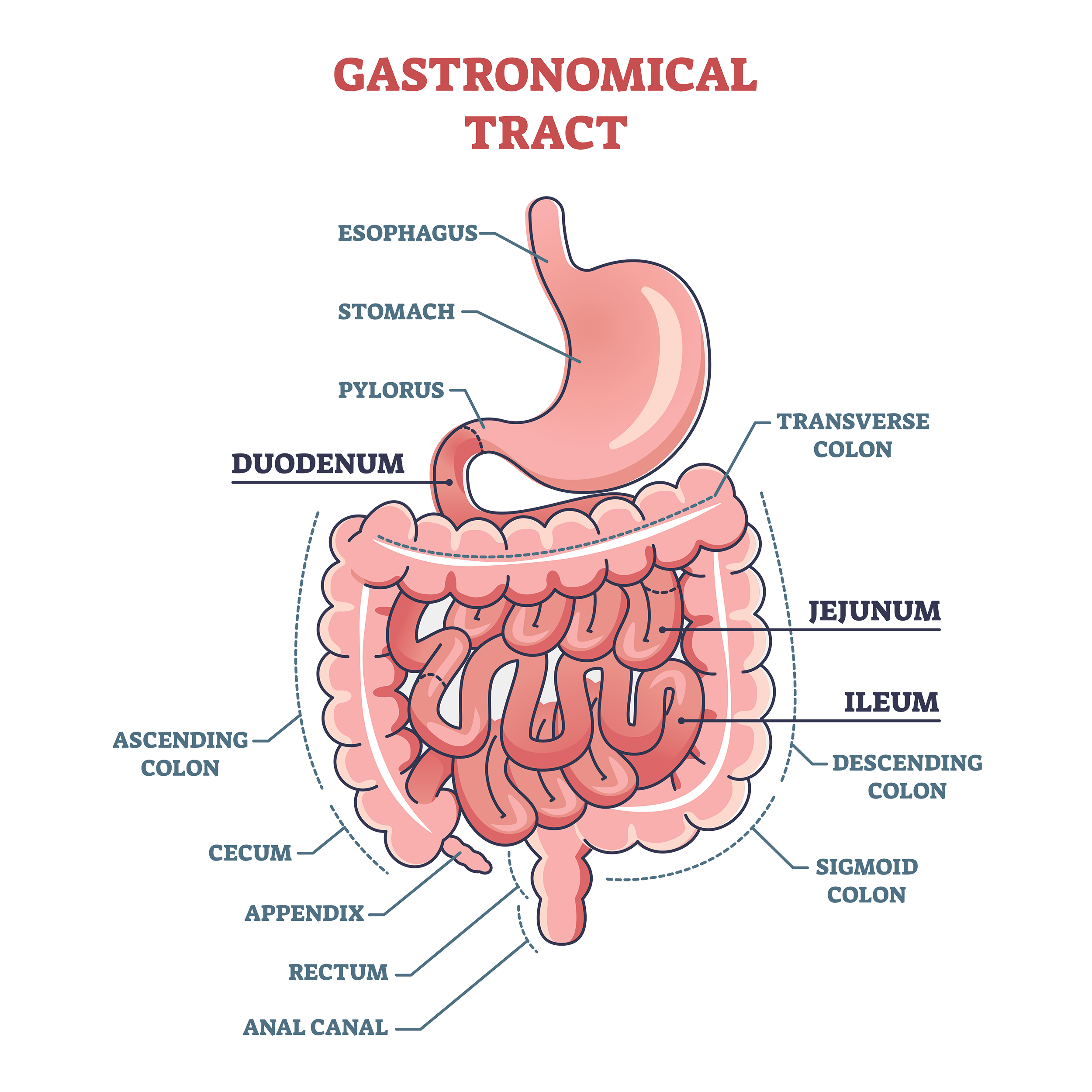

Anatomy

Esophagus

The esophagus is a long, muscular tube of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract that transports food and liquids from the mouth to the stomach. It can be divided further into the cervical esophagus and upper/middle/lower thoracic esophagus.

The two main types of cancers of the esophagus are squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adenocarcinoma (AC). They differ in the type of cell from which the cancer originates – SCC arises from the flat cells that line the esophagus whereas AC arises from glandular cells that produce mucus and fluids, usually found in the lower esophagus near the stomach.

Esophageal cancer is the 8th and 19th most commonly diagnosed cancer in the world and Canada, respectively. Although it is considered a rare cancer in Canada, the incidence of esophageal AC has doubled over the past two decades whereas esophageal SCC is steadily decreasing.

Main risk factors for developing esophageal SCC in Western countries are smoking and heavy alcohol consumption. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and obesity have been found to increase risk of developing esophageal AC.

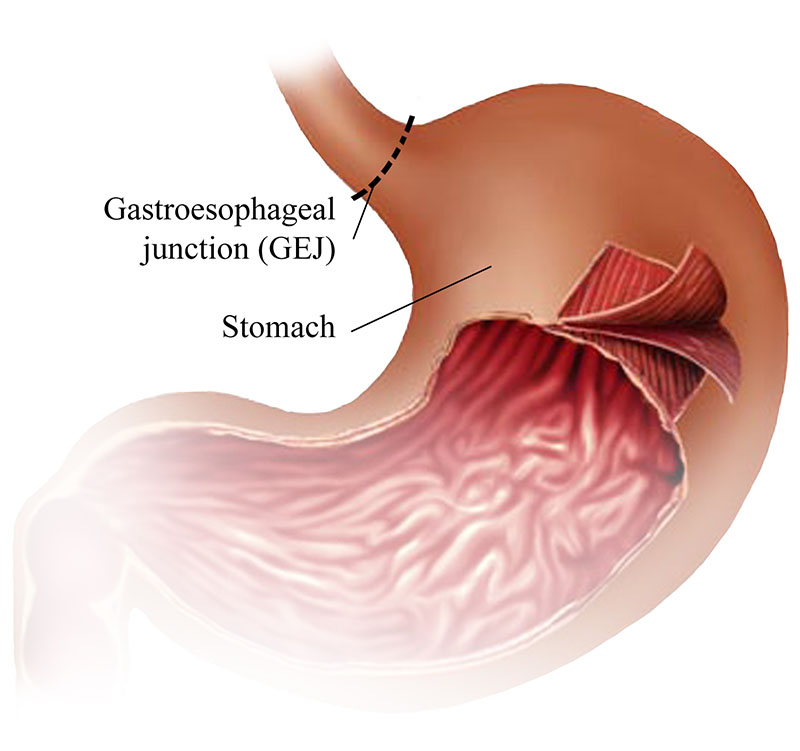

Gastroesophageal Junction

The gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) is where the esophagus meets the stomach. This is a common area where Barrett’s esophagus can develop, a condition caused by chronic GERD. Adenocarcinoma is the main type of cancer that arises from the GEJ.

Stomach

The stomach is a J-shaped organ that plays a central role in digesting food and absorbing nutrients.The stomach is divided into the cardia, fundus, body, and pylorus.

95% of all stomach cancers are adenocarcinomas. The incidence of stomach cancer in Canada is low (around 4100 Canadians will be diagnosed each year), however, it is increasing in the developed world. Stomach cancer is much higher in other parts of the world, such as East and Central Asia and Latin America.

Main risk factors for developing gastric adenocarcinoma are diet (such as high consumption of salted, pickled, or smoked foods) and H. pylori infection.

References

Lagergren J, Smyth E, Cunningham D, Lagergren P. Oesophageal cancer. Lancet. 2017;390(10110):2383–96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31462-9

Pandeya N, Olsen CM, Whiteman DC. Sex differences in the proportion of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cases attributable to tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37(5):579–84. 10.1016/j.canep.2013.05.011

Hvid‐Jensen F, Pedersen L, Drewes AM, Sorensen HT, Funch‐Jensen P. Incidence of adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett’s esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(15):1375–83. 10.1056/NEJMoa1103042

Arnold M, Pandeya N, Byrnes G, Renehan PAG, Stevens GA, Ezzati PM, et al. Global burden of cancer attributable to high body‐mass index in 2012: a population‐based study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(1):36–46. 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71123-4

Rüdiger Siewert J, Feith M, Werner M, Stein HJ. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: results of surgical therapy based on anatomical/topographic classification in 1,002 consecutive patients. Ann Surg. 2000 Sep;232(3):353-61. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200009000-00007.

Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2022. Canadian Cancer Society; 2022: https://cancer.ca/en/research/cancer-statistics.

Rawla P, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of gastric cancer: global trends, risk factors and prevention. Prz Gastroenterol. 2019;14(1):26-38. doi: 10.5114/pg.2018.80001. Epub 2018 Nov 28. PMID: 30944675; PMCID: PMC6444111.

World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) Continuous Update Project Report: Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Stomach Cancer 2016. Revised 2018. London: World Cancer Research Fund International; 2008.

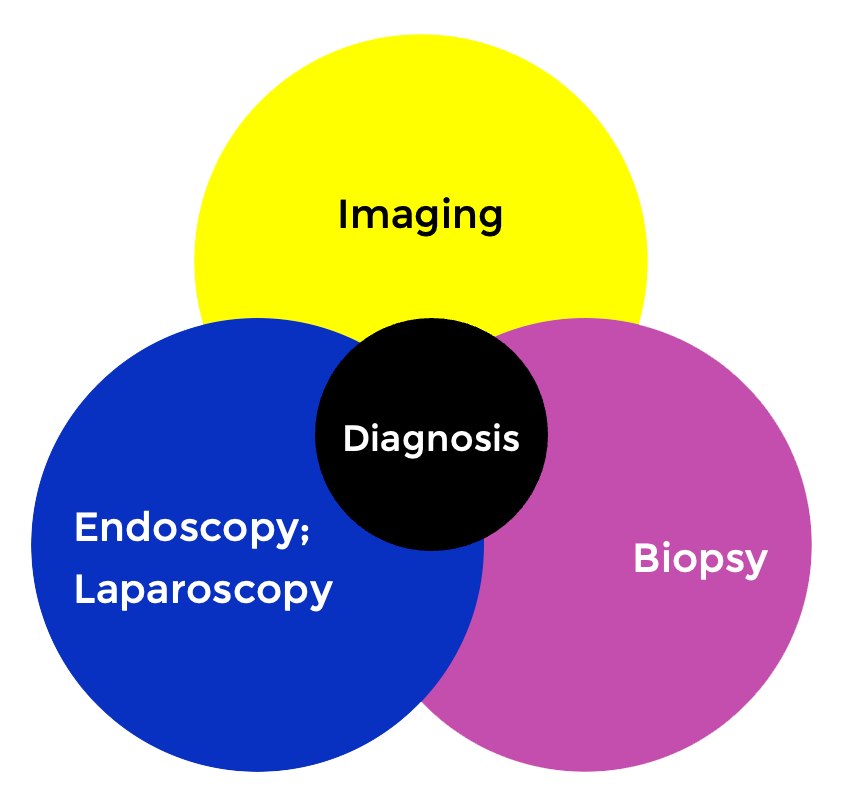

Diagnostic Tools

Confirming the type and stage of gastroesophageal cancer is important for your clinical team to treat your cancer. These tests and procedures are usually done at the same time.

Computed Tomography (CT) Imaging

CT scans use X-rays when scanning the 3D image of your body. This is used to complete staging of the cancer by looking at whether the cancer has spread to other parts of the body (e.g., liver, lung, distant lymph nodes). If the radiologist finds metastatic disease, this is considered to be stage IV cancer.

CT scans are also used to track response from your cancer treatment (radiation, chemotherapy, surgery). The frequency of these scans will depend on what treatment regimen you are on and if you are experiencing any worrisome symptoms such as bowel obstruction.

Positron-Emission Tomography (PET) Imaging

PET scans use a glucose-tracer to assess where there is very high metabolic activity in the body. As cancer uses a lot of energy to grow, the primary tumour and other metastatic sites will “light” up in the scans. PET scans are not often used in staging gastric cancers since it can miss peritoneal disease (the space outside the stomach).

Other Imaging

There may be other imaging tests that your doctor may order such as X-ray, bone scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasound before, during, and after treatment.

Endoscopy (also known as oesophagogastroscopy or gastroscopy)

In order to collect tumour tissue required for a pathological diagnosis, an endoscopy needs to be performed. During the endoscopy, a thin tube with a camera at the end will be guided down the mouth and to the esophagus and stomach. Endoscopists can also see whether there is active bleeding or obstruction caused by the tumour. This usually takes no more than 20 minutes. You will be given local sedation for the procedure and medication to make you drowsy.

Click here for information on how to prepare for your endoscopy.

Other tests can also be done during an endoscopy:

- Biopsy – small pieces of tumour tissue will be taken for pathological diagnosis, biomarker testing, and/or genetic sequencing.

- Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) – better view of the tumour and how deep it invades the wall of the esophagus or stomach. Local lymph nodes and nearby structures will also be assessed to determine whether there is spread of cancer.

- Dilatation – usually done if there is treatment-induced stricture of the upper GI tract or whether there is tumour obstruction,

- Esophageal stenting – may be inserted to keep the esophagus or GE junction open if other treatments (e.g., dilatation) are ineffective at opening the stricture.

- Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) – this is performed in patients whose cancer is treated with curative intent and have very early stage esophageal/GE junction cancers.

Image-guided biopsy

This is sometimes needed to confirm whether suspicious-looking lesions on your CT and/or PET scans are cancerous. Tissue is taken during the procedure and sent to pathology to confirm whether there are cancer cells. If it is cancerous, it can be used for tumour biomarker testing and genetic sequencing. Liver, lung, peritoneal, and lymph node biopsies are most common in gastroesophageal cancers.

The actual procedure takes approximately 20 minutes and is usually performed while you are awake. The radiologist and nurses will give you local anesthesia and sedation. A thin needle guided by ultrasound or CT imaging will be inserted through the skin for tissue collection.

Click here for information on how to prepare for your biopsy.

Laparoscopy

This procedure is done in patients with gastric cancer to rule out whether cancer has spread to the peritoneum (the cavity that holds your stomach and other organs). A thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing is inserted into the abdominal cavity. If there are any suspicious-looking nodules, a biopsy will be done and the tissue will be sent to pathology to confirm whether it is cancerous. A peritoneal wash will also be done, which consists of washing the cavity with saline and collecting the fluid to detect if there are any cancerous cells floating inside the peritoneum.

The actual procedure takes approximately 30 minutes. You will be given general anesthesia to fall asleep during the procedure. Sometimes, an endoscopy is also done in addition to this procedure.

Pathology

A pathological diagnosis of your cancer will require tissue from your suspected tumour. Tissue is usually retrieved from the primary tumour (esophagus, GEJ, or stomach) during an endoscopy or a metastatic lesion during an image-guided biopsy or laparoscopy.

Once the tissue is collected, a pathologist will cut the tissue on slides and perform special staining on them and look at them under a microscope to:

- Confirm cancer cells

- Classify the type of cancer (squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma), the tumour grade and subtype

- Perform additional tumour biomarker analyses for targeted therapy

Tumour Biomarkers in Gastroesophageal Cancers

Below is a list of biomarkers that are common in gastroesophageal cancers and testing for them have been clinically validated in Canada. Testing is done on the tumour tissue that is taken during your biopsy. Depending on the results, your medical oncologist may choose to add targeted therapy and/or immunotherapy to your treatment regimen.

HER2 (Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2)

HER2 may be made in larger than normal amounts by some types of cancer cells, including breast, ovarian, bladder, pancreatic, stomach, and esophageal cancers. This may cause cancer cells to grow more quickly and spread to other parts of the body. Checking the amount of HER2 on some types of cancer cells may help plan treatment. Also called c-erbB-2, HER2/neu, human EGF receptor 2, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

MMR (Mismatch repair) Deficiency

Describes cells that have mutations (changes) in certain genes that are involved in correcting mistakes made when DNA is copied in a cell. Mismatch repair (MMR) deficient cells usually have many DNA mutations, which may lead to cancer. MMR deficiency is most common in colorectal cancer, other types of gastrointestinal cancer, and endometrial cancer, but it may also be found in cancers of the breast, prostate, bladder, and thyroid and in an inherited disorder called Lynch syndrome. Knowing if a tumor is MMR deficient may help plan treatment or predict how well the tumor will respond to treatment. Also called deficient DNA mismatch repair, deficient mismatch repair, dMMR, and mismatch repair deficiency.

PD-L1

A protein that acts as a kind of “brake” to keep the body’s immune responses under control. PD-L1 may be found on some normal cells and in higher-than-normal amounts on some types of cancer cells. When PD-L1 binds to another protein called PD-1 (a protein found on T cells), it keeps T cells from killing the PD-L1-containing cells, including the cancer cells. Anticancer drugs called immune checkpoint inhibitors bind to PD-L1 and block its binding to PD-1. This releases the “brakes” on the immune system and leaves T cells free to kill cancer cells.

CLDN 18.2 (Claudin 18.2)

CLDN18.2 is a tight junction protein and stomach-specific isoform of claudin-18, is expressed on a variety of tumor cells. Its expression in healthy tissues is strictly confined to short-lived differentiated epithelial cells of the gastric mucosa.

Resource: National Cancer Institute

Cancer Staging

Like many other cancers, gastroesophageal cancers use a staging system which will guide your doctors on the type of treatment plan they will propose. In North America, we use the TNM guidelines proposed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual.

- T stage = depth of tumour invasion

- N stage = number of regional lymph nodes involved

- M stage = whether the cancer has spread to distant lymph nodes and/or organs

With the information above, your oncologist can determine the overall staging of your cancer and provide treatment:

- Stage I-III = Cancer is present. The higher the number, the larger the cancer tumor and the more it has spread into nearby tissues.

- Stage IV = Cancer has spread to distant parts of the body.

Clinical vs pathological staging – what does it mean?

- Clinical staging is often performed using CT scans and endoscopic ultrasounds to evaluate the depth of invasion and whether the cancer is spread to lymph nodes and other organs. This may not be accurate as it cannot detect micro-metastatic disease (cancer cells in other parts of the body too small to be seen by imaging).

- Pathological staging is performed by taking tissue from surgeries/biopsies and looking at the tissue under the microscope. This is more accurate as it allows the doctor to see cancer cells that are too small to be seen in imaging scans. It also allows doctors to see whether there is treatment response to chemotherapy/radiotherapy.

References:

Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR, Winchester DP. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017 Mar;67(2):93-99. doi: 10.3322/caac.21388. Epub 2017 Jan 17. PMID: 28094848.

Treatment

Treatment as well as treatment intent will vary depending on the type and stage of your cancer as well as your values and preferences. In gastroesophageal cancer, a combination of systemic therapy, radiation, and surgery may be presented to you by your clinical team.

Systemic Treatment

Systemic treatment is a drug therapy prescribed by a medical oncologist– either given intravenously or orally. For gastroesophageal cancer patients, systemic treatment will most likely be part of your treatment plan. The purpose of systemic therapy is to shrink and control the cancer. The type of agents used will depend on whether systemic therapy is used for curative or palliative intent. Since systemic therapy is delivered to the whole body, it can kill cancer cells that may have metastasized to other parts of the body that are missed by imaging or biopsy tests.

There are different types of standard-of-care systemic therapy and patients can receive a combination of them depending on the biology of the tumour:

Chemotherapy

Below is a list of common chemotherapy regimens for gastroesophageal cancer (Click on each for more information):

Targeted therapy/Immunotherapy

If your tumour is positive for certain biomarkers, your medical oncologist may add targeted agents/immunotherapy in addition to your chemotherapy (Click on each for more information):

Radiation Therapy

Radiation is a type of local therapy (treats only specific parts of the body) prescribed by a radiation oncologist. Depending on the type, location, and stage of your cancer, radiation may be offered as curative intent and/or controlling the symptoms caused by your cancer. It is often used in combination with systemic therapy.

Common symptoms or issues that may be alleviated by radiation are:

- Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing)

- Bleeding of the tumour

- Pain from metastases

- Neurological symptoms caused by brain metastases

Common Types of Radiation

External Beam Radiation Therapy

Resource: National Cancer Institute

External beam radiation therapy comes from a machine that aims radiation (high energy waves) at your cancer. The machine is large and may be noisy. It does not touch you, but can move around you, sending radiation to a part of your body from many directions. This is often done as an outpatient procedure and takes up to an hour.

The spot where all beams meet creates a high dose of radiation that targets the DNA in cancer cells which causes cell death.

Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT)

A type of external radiation therapy that uses special equipment to position a patient and precisely deliver radiation to tumors in the body (except the brain). The total dose of radiation is divided into smaller doses given over several days. This type of radiation therapy helps spare normal tissue

Please see below for more information on what to expect when getting radiation to specific body parts:

For more information on managing side effects related to radiation:

Surgery

Surgical resection of gastroesophageal tumours (gastrectomy/esophagectomy) are performed by specialized thoracic and general surgeons in patients with localized disease (cancer has not spread to distant body parts). There are some special circumstances in which tumour resection can be done in patients with stage IV cancer, such as salvage/palliative resection or metastectomy (removal of metastases) to alleviate disease burden and symptom management.

Curative-intent surgery is often combined with peri-operative treatment such as systemic therapy and/or radiation. The type of peri-operative treatment will depend on many things such as tumour location and type, cancer staging, co-morbidities, and physical status. The purpose of peri-operative treatment is to reduce the size of tumour before surgery and kill any cancer cells that may be circulating in your body (not seen by imaging).

Please see below for more information on the common surgeries performed in gastroesophageal cancers and other related topics.

Before Your Surgery:

Types of Surgery:

Common Side Effects

Please see below for more information on common side effects of treatment for gastroesophageal cancers.